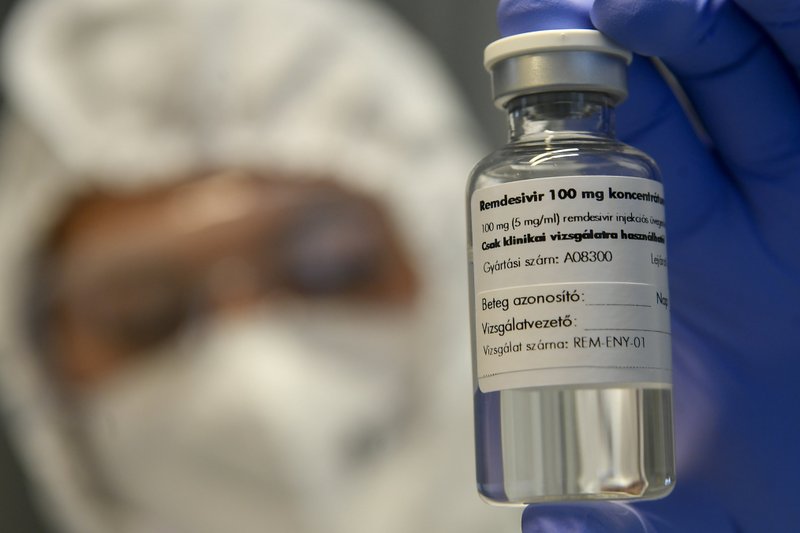

FILE – In this Thursday Oct. 15, 2020 file photo, A bottle containing the drug Remdesivir is held by a health worker at the Institute of Infectology of Kenezy Gyula Teaching Hospital of the University of Debrecen in Debrecen, Hungary. Health officials around the world are clashing over the use of certain drugs for COVID-19, leading to different treatment options for patients depending on where they live. The World Health Organization guidelines panel advised against using the antiviral remdesivir for hospitalized patients, saying there’s no evidence it improves survival or avoids the need for breathing machines. (Zsolt Czegledi/MTI via AP, File)

Health officials around the world are clashing over the use of certain drugs for COVID-19, leading to different treatment options for patients depending on where they live.

On Friday, a World Health Organization guidelines panel advised against using the antiviral remdesivir for hospitalized patients, saying there’s no evidence it improves survival or avoids the need for breathing machines.

But in the U.S. and many other countries, the drug has been the standard of care since a major, government-led study found other benefits — it shortened recovery time for hospitalized patients by five days on average, from 15 days to 10.

Within the U.S., a federal guidelines panel and some leading medical groups have not endorsed two other therapies the Food and Drug Administration authorized for emergency use — Eli Lilly’s experimental antibody drug and convalescent plasma, the blood of COVID-19 survivors. The groups say there isn’t enough evidence to recommend for or against them.

Doctors also remain uncertain about when and when not to use the only drugs known to improve survival for the sickest COVID-19 patients: dexamethasone or similar steroids.

And things got murkier with Thursday’s news that the anti-inflammatory drug tocilizumab may help. Like the key WHO study on remdesivir, the preliminary results on tocilizumab have not yet been published or fully reviewed by independent scientists, leaving doctors unclear about what to do.

“It’s a genuine quandary,” said the University of Pittsburgh’s Dr. Derek Angus, who is involved in a study testing many of these treatments. “We need to see the details.”

Dr. Rochelle Walensky, infectious disease chief at Massachusetts General Hospital, agreed.

“It’s really hard to practice medicine by press release,” she said on a podcast Thursday with a medical journal editor. Until the National Institutes of Health’s guidelines endorse a treatment, “I’m really reluctant … to call that standard of care.”

Angus said there are legitimate questions about all of the drug studies.

“It’s not unusual for professional guidelines to disagree with each other, it’s just that it’s all under the microscope with COVID-19,” he said.

The rift over remdesivir, sold as Veklury, by Gilead Sciences Inc., is the most serious. The WHO guidelines stress that the drug does not save lives, based heavily on a WHO-sponsored study that was larger but much less rigorous than the U.S.-led one that found it had other benefits.

The drug is given through an IV for around five days, and its high cost and lack of “meaningful effect” on mortality make it a poor choice, the WHO panel concluded.

Gilead charges $3,120 for a typical treatment course for patients with private insurance and $2,340 for people covered by government health programs in the U.S. and other developed countries. In poor or middle-income countries, much cheaper versions are sold by generic makers.

This week, the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review, a nonprofit group that analyzes drug prices, said remdesivir should be priced around $2,470 for hospitalized patients with moderate to severe disease because of the cost savings from fewer days of care. However, it’s worth only $70 for patients hospitalized with milder disease, the group concluded.

Price also may be driving lower demand. In October, U.S. health officials said that hospitals had bought only about one-third of the doses of remdesivir that they were offered over the previous few months, when the drug was in short supply. Between July and September, 500,000 treatment courses were made available to state and local health departments but only about 161,000 were bought.

In a separate development, the FDA on Thursday gave emergency authorization to use of another anti-inflammatory drug, baricitinib, to be used with remdesivir. Adding baricitinib shaved an additional day off the average time to recovery for severely ill hospitalized patients in one study.

Lilly sells baricitinib now as Olumiant to treat rheumatoid arthritis, the less common form of arthritis that occurs when a mistaken or overreacting immune system attacks joints, causing inflammation. An overactive immune system also can lead to serious problems in coronavirus patients.

Marilynn Marchione can be followed on Twitter at http://twitter.com/MMarchioneAP

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Department of Science Education. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

Copyright 2020 Associated Press. All rights reserved.