Major breaches over the past year were a double-edged sword in efforts to pass a crucial mandatory reporting measure that didn’t make it into the ‘must-pass’ legislation despite bipartisan support, according to key lawmakers.

President Joe Biden on Monday signed into law the National Defense Authorization Act of 2022 which codifies an approach to cybersecurity that depends on the decisions of private-sector entities to protect the bulk of the nation’s critical infrastructure.

The NDAA has become the go-to legislative vehicle for efforts to manage the federal government at large, and to regulate the private sector on cybersecurity issues.

On the government side, the law requires the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency to biennially update an incident response plan and to consult with sector-specific agencies and the private sector in establishing an exercise program to assess its effectiveness.

It seeks to “ensure that the National Guard can provide cyber support services to critical infrastructure entities—including local governments and businesses,” according to Sen. Maggie Hassan, D-N.H. It also establishes a grant program at the Homeland Security Department to foster collaboration on cybersecurity technologies between public and private-sector entities in the U.S. and Israel.

Lawmakers also highlighted the inclusion of provisions codifying existing public-private partnerships at CISA which aim to offer continuous monitoring of industrial control systems—an effort known as the CyberSentry program—and to develop ‘know your customer’ guidelines for companies like cloud and other service providers comprising the “internet ecosystem.” Such companies are described as the plank bearers of CISA’s Joint Cyber Defense Collaborative.

But provisions all rely on the voluntary participation by industry, which owns and operates the vast majority of the nation’s critical infrastructure. Despite bipartisan calls after massive breaches at SolarWinds, Microsoft Exchange, Colonial Pipeline and other hacks, the NDAA made it through the House without mandatory incident reporting requirements for the private sector.

“The NDAA takes important steps on cybersecurity, particularly to promote strengthened public-private sector partnerships across the government,” Laura Brent, a senior fellow at the Center for a New American Security, said after the Senate passed the same legislation a week later. “Given the scale of the cyber challenge, however, the NDAA lacks the necessary sustained urgency. Most significantly, requirements for even some industry reporting of cyber incidents and ransomware payments to the government were not included—despite being key for the government to get better insight into cyber threats.”

The legislation requiring reporting also had significant industry support after companies successfully appealed to lawmakers to extend the window for reporting incidents to CISA and to exclude financial penalties as an enforcement mechanism.

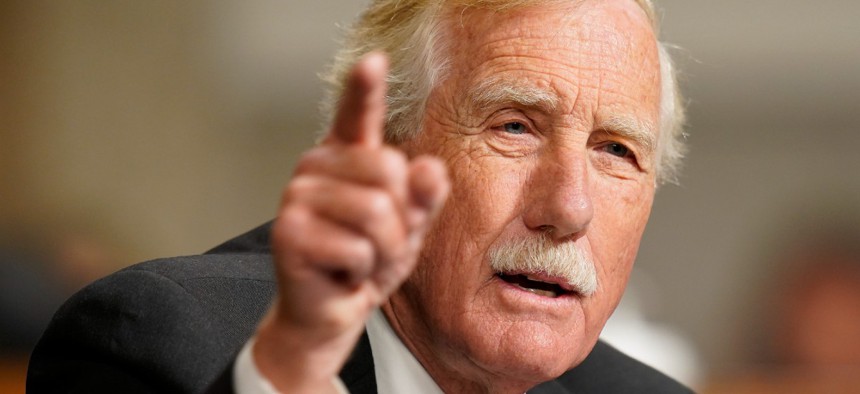

On a Dec. 22 call with reporters, Rep. Mike Gallagher, R-Wis., and Sen. Angus King, I-Maine—co-chairs of the now sunsetted Cyberspace Solarium Commission, which succeeded in creating the National Cyber Director post through last year’s NDAA—said the insurmountable hurdle was the tight control committee leadership likes to keep over their jurisdictions.

Last year, “we had to get 180 clearances from both sides of committees and subcommittees on both houses of Congress, that gives you a flavor of how complex this process is,” King said.

In that situation, you just run out of time on the clock, Gallagher said. The lawmakers said the attention on cybersecurity after the high-profile attacks this year both helped and hurt matters. But both agreed that on balance it was a good thing.

The incidents “made it clear to everyone that what we’re talking about here is not an academic problem, an abstract problem, but a very clear and present problem,” King said. “I think that helped us overall. The downside, if you want to call it that, is that you do have more people who are engaged and more people who want to be consulted, want to be worked with, want to be involved in the process. But, you know, I’ll take that. I think that’s a trade off, but I think that’s an OK trade off.”

Gallagher was optimistic about the prospects for more ambitious cybersecurity legislation next year.

“Even where we weren’t able to get something in NDAA, we did make a lot of progress in clearing certain committee jurisdictional hang ups and engaging with our colleagues who just may not have been tracking the legislation and sort of reflexively opposed it,” he said.