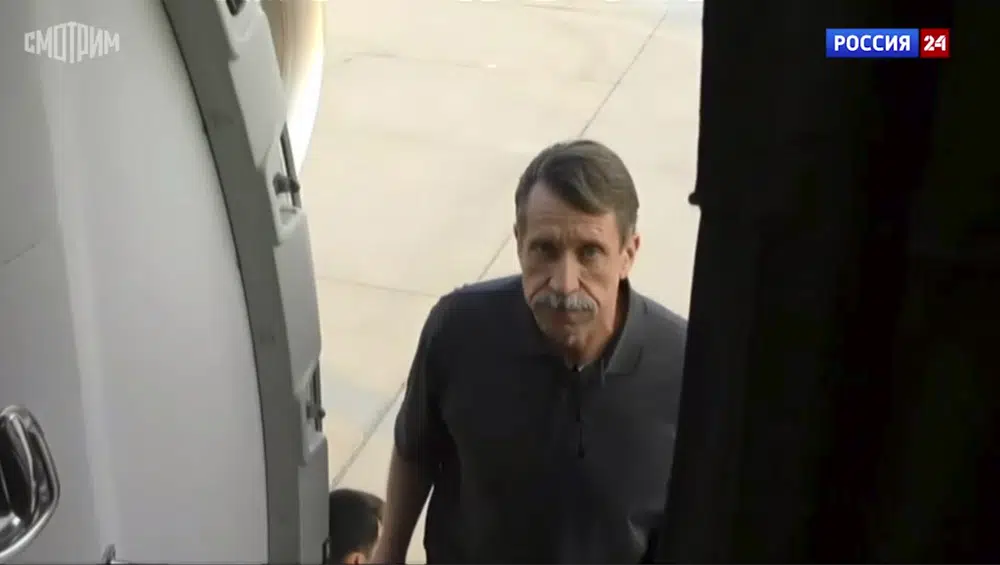

In this image taken from video provided by the RU-24 Russian Television on Friday, Dec. 9, 2022, Russian citizen Viktor Bout, right, who was exchanged for U.S. basketball player Brittney Griner, boards a Russian plane after a swap, in the airport of Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. Russian arms dealer Bout, who was released from U.S. prison in exchange for WNBA star Griner, is widely labeled abroad as the “Merchant of Death” who fueled some of the world’s worst conflicts but seen at home as a swashbuckling businessman unjustly imprisoned after an overly aggressive U.S. sting operation. (RU-24 Russian Television via AP)

WASHINGTON (AP) — A Taliban drug lord convicted in a vast heroin trafficking conspiracy. A Russian pilot imprisoned for a scheme to distribute cocaine across the world. And a Russian arms dealer so infamous that he earned the nickname “Merchant of Death.”

Those are just some of the convicted felons the United States government has agreed to release in the last year in exchange for securing the release of Americans detained abroad. It’s long been conventional wisdom that the U.S. risks incentivizing additional hostage taking by negotiating with adversarial nations and militant groups for the release of American citizens. But the succession of swaps has made clear the Biden administration’s willingness to free a convicted criminal once seen as a threat to society if that’s what it takes to bring home a U.S. citizen.

The latest swap occurred Thursday when WNBA star Brittney Griner, a two-time Olympic gold medalist who played pro basketball in Russia and was easily the most prominent American to be held overseas, was freed in exchange for Russian arms dealer Viktor Bout.

The exchange drew some criticism, including from Republican lawmakers, and raised concerns that Bout, who was tried and convicted in American courts, was being traded for someone the U.S regarded as a wrongful detainee convicted in Russia of a relatively minor offense. Administration officials acknowledged that such deals carry a heavy price and cautioned against the perception that they are the new norm, but the reality is that they’ve been a tool of administrations of both political parties.

The Trump administration, seen as more willing to flout convention in hostage affairs, brought home Navy veteran Michael White in 2020 in an agreement that freed an Iranian American doctor and permitted him to return to Iran.

The Obama administration pardoned or dropped charges against seven Iranians in a prisoner exchange tied to the nuclear deal with Tehran. Three jailed Cubans were sent home in 2014 as Havana released American Alan Gross after five years’ imprisonment.

Jon Franks, who’s long advised families of American hostages and detainees, said it’s not true that the U.S. can just throw its might around and get people released.

“The maximum pressure mantra just doesn’t work — and, by the way, I don’t think prisoner trades undercut maximum pressure,” said Franks, the spokesman for the Bring Our Families Home Campaign.

Griner was arrested at a Moscow airport in February after customs agents said she was carrying vape canisters with cannabis oil. Bout, who was arrested in 2008, was sentenced in 2012 to 25 years in prison on charges that he conspired to sell tens of millions of dollars in weapons that U.S officials said were to be used against Americans.

The trade highlights a trend in recent years of Americans being detained abroad and held hostage not by terrorist groups but by countries looking to gain leverage over America, said Dani Gilbert, a fellow in U.S. foreign policy and international security at Dartmouth College.

Gilbert said the idea that the U.S. doesn’t negotiate for hostages is a “misnomer.” She said that really only applies when an American is being held by a U.S.-designated terrorist organization, but otherwise the U.S. has historically done whatever is necessary to bring Americans home.

What is different, she said, is over roughly the last decade there’s been a trend of foreign governments as opposed to terrorist groups detaining Americans abroad, often on trumped-up charges. She noted that in July the U.S. introduced a new risk indicator on its travel advisories — a “D” — for countries that tend to wrongfully detain people.

“Currently there are about four dozen Americans who are considered wrongfully detained, which puts them in this category essentially of being held wrongfully or unlawfully by a foreign government, perhaps for leverage,” she said. “Those cases have really been on the rise in recent years.”

Gilbert said she was nervous that trades like the Griner-Bout deal would encourage other authoritarian leaders to use similar tactics.

During a ceremony Thursday celebrating Griner’s release, President Joe Biden urged Americans to take precautions before traveling overseas.

“We also want to prevent any more American families from suffering this pain and separation,” he said.

Bout earned the nickname “Merchant of Death” for supposedly supplying weapons for civil wars in South America, the Middle East and Africa.

But Shira A. Scheindlin, the former federal judge who sentenced Bout, said while he had a history as an international arms dealer selling weapons to unsavory characters, at the time of his arrest in a U.S. sting operation he appeared to be largely out of the business.

“We’re not talking about someone who at that point in his career was actively dealing arms to terrorists,” she said.

Scheindlin said during an interview after Bout was released that she thought that the time he had spent behind bars was adequate punishment. She said she always thought Bout’s sentence was too long and she would have given him a lesser one if she hadn’t been confined by statutory mandatory minimums.

The attention paid to Griner’s case has raised questions about whether her celebrity and the public pressure it generated pushed the Biden administration to make a deal where it hasn’t in other cases. Left out of the deal was Paul Whelan, a Michigan corporate security executive who had regularly traveled to Russia until he was arrested in December 2018 in Moscow and convicted of what the U.S. government says are baseless espionage charges.

Jared Genser, a Washington lawyer who represents the family of Siamak Namazi, who has been held in Iran since 2015, said Griner’s celebrity undoubtedly gave her supporters access to the highest levels of American power in a way that few others get. That also showed Vladimir Putin how “desperately the president wanted to get” Griner out, Genser said.

Elsewhere in the world, American citizens have been detained for years.

Saudi dissident Ali al-Ahmed, who runs the Washington-based Gulf Institute, has a cousin who was detained in Saudi Arabia in 2019 and was released earlier this year but still can’t leave the country. Al-Ahmed works to help other families with loved ones held in the oil-rich Gulf kingdom. He said detainees like his cousin don’t have the celebrity of someone like Griner, and he feels not enough attention is being paid by the U.S. government to them.

“They should not favor Americans of certain background over another American,” he said. “There has not been equality here.”

The family of another prominent American held overseas — Austin Tice — also expressed frustration in a statement Thursday. While they said they were happy that Griner had been released, they were “extremely disappointed” in the U.S. government’s lack of progress in Tice’s case. Tice went missing in Syria in 2012; Washington maintains Tice is being held by Syrian authorities, which the Syrians deny.

“If the U.S. government can work with Russia, there is no excuse for not directly engaging Syria,” the statement read. “God willing, Austin will not spend another Christmas alone in captivity.”

Copyright 2021 Associated Press. All rights reserved.