Militia members wait inside the Senate chamber at the Capitol building during the “American Patriot Rally on Capitol Lawn” protest in Lansing, Mich., Thursday April 30, 2020, during the coronavirus outbreak. Experts say far-right groups in the U.S. are taking a more dangerously radical turn as four men go on trial in an alleged scheme to kidnap Michigan’s governor. (Nicole Hester/Mlive.com/Ann Arbor News via AP, File)

TRAVERSE CITY, Mich. (AP) — They railed against politicians, conducted military-style exercises and spoke darkly of confronting tyrants scheming to seize their guns and enslave them.

Yet historian JoEllen Vinyard says the “citizen militia” activists she got to know in the 1990s didn’t seem like the types who would abduct a governor or stage a coup.

“I don’t think they were dangerous,” said Vinyard, an Eastern Michigan University professor emeritus and author of a book about far-right movements in the state. “They reminded me of the good old boys I knew growing up in Nebraska.”

But as four men charged with conspiring to kidnap Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer go on trial Tuesday in U.S. District Court in Grand Rapids, Vinyard and other political extremism scholars say things have changed in recent years. Their arrests came about three months before the Jan. 6, 2021, insurrection that led to charges against many right-wing extremists and militants.

In contrast to militants from before, who mostly avoided bloodshed with the horrific exception of the Oklahoma City bombing, some modern successors have taken a more radical and potentially violent turn.

“This is a different type of domestic terrorism phenomenon than we’ve faced in previous decades — completely different from anything I’ve observed,” said Javed Ali, a University of Michigan professor who served with the FBI and intelligence agencies.

“You’ve got all these points on a very diverse threat spectrum — not centralized in any one corner, no single groups, no national leadership, completely disorganized and disaggregated,” Ali said. “It’s difficult for law enforcement to spot these threats. The Whitmer plot is a case in point.”

The alleged kidnapping conspiracy involved members of a little-known cell called the “Wolverine Watchmen” and others who attended a July 2020 meeting in Ohio of self-styled “militia” leaders from several states, according to court documents.

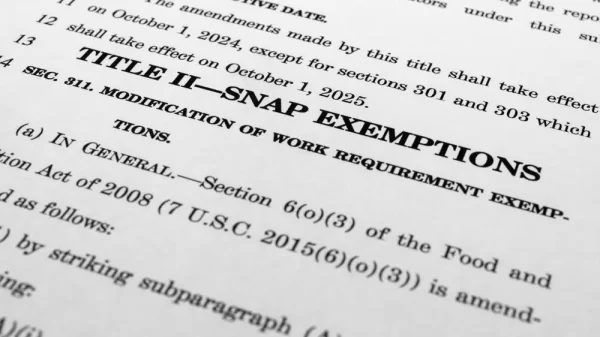

They were angry about pandemic lockdowns and other policies they considered dictatorial, investigators said. Some had joined a protest months earlier at the Michigan Capitol in Lansing, where armed demonstrators faced off with police and some carried guns into the Senate gallery.

Federal prosecutors in October 2020 charged six suspects in the alleged plot, including Ty Garbin and Kaleb Franks, who have pleaded guilty. Garbin received a six-year prison term; Franks will be sentenced later.

The other four defendants are Adam Fox, Daniel Harris, Brandon Caserta and Barry Croft Jr. All are Michigan residents except Croft, who is from Delaware.

Eight other men accused of aiding the conspiracy have been charged in state court.

The Wolverine Watchmen are among the small, secretive groups that have appeared in Michigan since the initial burst of paramilitary activism faded, Ali said.

They began recruiting members on Facebook in November 2019 and communicated through an encrypted messaging platform, according to a state police affidavit. It said they held firearms training and tactical drills to prepare for “the boogaloo,“ an anticipated “uprising against the government or impending politically motivated civil war.”

The scheme against Whitmer was hatched the following summer during a meeting at which Watchmen discussed invading the statehouse and using explosives to distract law enforcement, Garbin acknowledged in his plea agreement.

They considered executing the Democratic governor or putting her on trial, eventually deciding to abduct her at her family’s vacation home in northern Michigan, the document said. Informants and undercover agents helped foil the alleged plot.

Vinyard, who attended meetings of self-described militia groups in southeastern Michigan for her research during the 1990s, said threatening language was rare then.

Members had long lists of grievances, some targeting the United Nations and a federal government they believed had exceeded its constitutional authority, she said. But others involved local law enforcement and courts.

“People talked about police harassment, truckers getting stopped by cops, fathers who had not been treated fairly when they got divorced and couldn’t see their kids,” she said.

Norman Olson, an Air Force veteran, gun shop owner and Baptist preacher who initially led the Michigan Militia, said then its members were outraged by deadly sieges involving federal agents at Ruby Ridge, Idaho, and Waco, Texas.

The militia drew international attention after the 1995 bombing of the Oklahoma City federal building, which killed 168 people. Timothy McVeigh and Terry Nichols, convicted in the case, had attended meetings in Michigan. Olson said they’d been kicked out for advocating violence.

By the early 2000s the movement appeared to lose steam, experts said, perhaps because of public revulsion over the bombing, internal strife, the presidency of gun-friendly George W. Bush and a crackdown on terrorism after the 9/11 attacks.

Following President Barack Obama’s election, it resurfaced on a wave of right-wing populism embodied by the Tea Party movement and Donald Trump that crested amid fury at COVID-19 restrictions.

In 2010, the FBI charged nine members of a fundamentalist Christian sect in southeastern Michigan called Hutaree with conspiring to rebel against the government. The judge dismissed most of the case, but it signaled what some observers describe as the rise of a more incendiary segment of the far right.

Even other paramilitary groups were uneasy with the Hutaree and notified authorities, according to a paper by Vanderbilt University sociologist Amy Cooter, who studies right-wing militancy.

Lee Miracle, a longtime leader of the Southeast Michigan Volunteer Militia, urged restraint in a statement on the group’s website after the Wolverine Watchmen arrests in 2020.

“Our capacity for violence, as a free people, should always be well maintained, and kept within reach, but it should always be the LAST option,” said Miracle, who did not return an email seeking additional comment.

But organizations that track the more belligerent groups say they’ve made inroads in Michigan, which has an extensive history as a far-right breeding ground.

The nonprofit Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project says among the most active are newcomers such as the Boogaloo Boys and the Proud Boys, a self-described “Western chauvinist” association. Another is the Michigan Liberty Militia, which had a visible presence at the state Capitol protest.

The movement has splintered into many factions over the years because of leadership rivalries and ideological differences, said retired FBI agent Greg Stejskal, who dealt with the Michigan Militia in its early days. Still, it has remained overwhelmingly white, male and rooted in conspiratorial fear of losing guns and freedom.

“They feel like they’re subjugated, and this is their way of fighting back,” he said.

They’ve kept a somewhat lower profile since the kidnapping arrests and the invasion of the U.S. Capitol by Trump supporters seeking to overturn the 2020 election, said Rachel Goldwasser, a research analyst with the nonprofit Southern Poverty Law Center.

The outcome of the Michigan conspiracy trial, she said, may “indicate whether they stay in their foxholes or come out as a force in public again.”

Copyright 2021 Associated Press. All rights reserved.