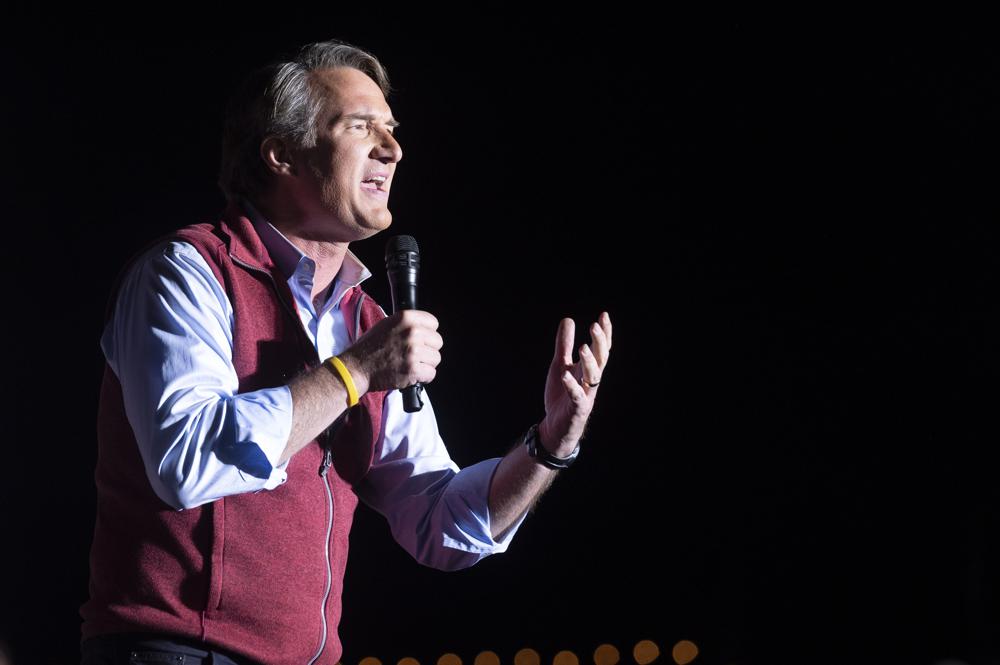

Then-Republican gubernatorial candidate Glenn Youngkin addresses supporters at a campaign rally in Leesburg, Va., on Nov. 1, 2021. Republicans plan to forcefully oppose race and diversity curricula in public schools as a core piece of their strategy in the 2022 midterm elections. The party is supercharging a message that helped catapult Republican Glenn Youngkin to a win in Virginia’s governor’s race. (AP Photo/Cliff Owen)

WASHINGTON (AP) — Republicans plan to forcefully oppose race and diversity curricula — tapping into a surge of parental frustration about public schools — as a core piece of their strategy in the 2022 midterm elections, a coordinated effort to supercharge a message that mobilized right-leaning voters in Virginia this week and which Democrats dismiss as race-baiting.

Coming out of Tuesday’s elections, in which Republican Glenn Youngkin won the governor’s office after aligning with conservative parent groups, the GOP signaled that it saw the fight over teaching about racism as a political winner. Indiana Rep. Jim Banks, chairman of the conservative House Study Committee, issued a memo suggesting “Republicans can and must become the party of parents.” House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy announced support for a “Parents’ Bill of Rights” opposing the teaching of “critical race theory,” an academic framework about systemic racism that has become a catch-all phrase for teaching about race in U.S. history.

“Parents are angry at what they view as inappropriate social engineering in schools and an unresponsive bureaucracy,” said Phil Cox, a former executive director of the Republican Governors Association.

Democrats were wrestling with how to counter that message. Some dismissed it, saying it won’t have much appeal beyond the GOP’s most conservative base. Others argued the party ignores the power of cultural and racially divisive debates at its peril.

They pointed to Republicans’ use of the “defund the police” slogan to hammer Democrats and try to alarm white, suburban voters after the demonstrations against police brutality and racism that began in Minneapolis after the killing of George Floyd. Some Democrats blame the phrase, an idea few in the party actually supported, for contributing to losses in House races last year.

If the party can’t find an effective response, it could lose its narrow majorities in both congressional chambers next November.

The debate comes as the racial justice movement that surged in 2020 was reckoning with losses — a defeated ballot question on remaking policing in Minneapolis, and a series of local elections where voters turned away from candidates who were most vocal about battling institutional racism.

“This happened because of a backlash against what happened last year,” said Bernice King, the daughter of the the late civil rights leader Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. who runs Atlanta’s King Center.

King warned attempts to roll back social justice advances are “not something that we should sleep on.”

“We have to be constantly vigilant, constantly aware,” she said, “and collectively apply the necessary pressure where it needs to be applied to ensure that this nation continues to progress.”

Banks’ memo included a series of recommendations on how Republicans aim to mobilize parents next year, and many touch openly on race. He proposed banning federal funding supporting critical race theory and emphasizing legislation ensuring schools are spending money on gifted and talented and advanced placement programs “instead of exploding Diversity, Equity and Inclusion administrators.”

Democrats plan to combat such efforts by noting that many top Republicans’ underlying goal is removing government funding from public schools and giving it to private and religious alternatives. They also see the school culture war squabbles as likely to alienate most voters since the vast majority of the nation’s children attend public schools.

“I think Republicans can, will continue to try to divide us and don’t have an answer for real questions about education,” said Marshall Cohen, the Democratic Governors Association’s political director. “Like their plan to cut public school funding and give it to private schools.”

White House deputy press secretary Karine Jean-Pierre accused Republicans of “cynically trying to use our kids as a political football.” But Jean-Pierre also took on conservatives’ critique that critical race theory teaches white children to be ashamed of their country.

“Great countries are honest, right? They have to be honest with themselves about the history, which is good and the bad,” she told reporters. “And our kids should be proud to be Americans after learning that history.”

Most schools don’t teach critical race theory, which centers on the idea that racism is systemic in the nation’s institutions and that they function to maintain the dominance of white people.

But parents organizing across the country say they see plenty of examples of how schools are overhauling the way they teach history and gender issues — which some equate with deeper social changes they do not support.

And concerns over what students are being taught — especially after remote learning amid the coronavirus pandemic exposed a larger swath of parents to curricula — led to other objections about actions taken by schools and school boards. Those including COVID safety protocols and policies regarding transgender students.

“I’m sure that most people have no problem with teaching history in a balanced way,” said Georgia Democratic Rep. Hank Johnson. “But when you say critical race theory, and you say that it is attacking us and causing our children to feel bad about themselves, that is an appeal that is attractive. And, unfortunately for Democrats, it’s hard to defend when someone accuses you of that.”

Democrats were wiped out Tuesday in lower-profile races in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, where critical race theory was a dominant issue at contentious school board meetings for much of the summer and fall.

Patrice Tisdale, a Jamaican-born candidate for magisterial district judge, said she felt the political climate was racially charged. She heard “dog whistles” from voters, who called her “antifa” and accused her of wanting to defund the police, she said. While canvassing a neighborhood in the election’s closing weeks, one voter asked Tisdale whether she believed in critical race theory.

“I said, ’What does that have to do with my election?’” recalled Tisdale, an attorney, who lost her race. “I’m there all by myself running to be a judge and that was her question.”

The issue had weight in Virginia, too. A majority of voters there — 7 in 10 — said racism is a serious problem in U.S. society, according to AP VoteCast, a survey of Tuesday’s electorate. But 44% of voters said public schools focus “too much” on racism in the U.S., while 30% said they focus on racism “too little.”

The divide along party lines was stark: 78% of Youngkin voters considered the focus on racism in schools to be too much, while 55% of voters for his opponent, Democrat Terry McAuliffe, said it was too little.

Youngkin strategist Jeff Roe described the campaign’s message on education as a broad, umbrella issue that allowed the candidate to speak to different groups of voters — some worried about critical race theory, others about eliminating accelerated math classes, school safety and school choice.

“It was about parental knowledge,” he said.

McAuliffe went on the attack last week, portraying Republicans as wanting to ban books. He accused Youngkin of trying to “silence” Black authors during a flareup over whether the themes in Nobel laureate’s Toni Morrison’s 1987 novel “Beloved” were too explicit. McAuliffe still lost a governor’s race in a state President Joe Biden carried easily just last year.

Republican Minnesota Rep. Tom Emmer bristled at equating a movement to defend school “parental rights” and race.

“The way this was handled in Virginia was frankly about parents, mothers and fathers, saying we want a say in our child’s education,” said Emmer, chairman of the National Republican Congressional Committee.

That didn’t rattle some Democrats, who see the GOP argument as manufactured and fleeting.

“Republicans are very good at creating issues,” deadpanned Democratic Michigan Sen. Debbie Stabenow.

“We’ll have to address it, and then they’ll make up something else.”

Beaumont reported from Des Moines, Iowa; Morrison from New York. Associated Press writers Steve Peoples in Doylestown, Pennsylvania, Jill Colvin in New York and Kevin Freking, Mary Clare Jalonick and Hannah Fingerhut in Washington contributed to this report.

Copyright 2021 Associated Press. All rights reserved.