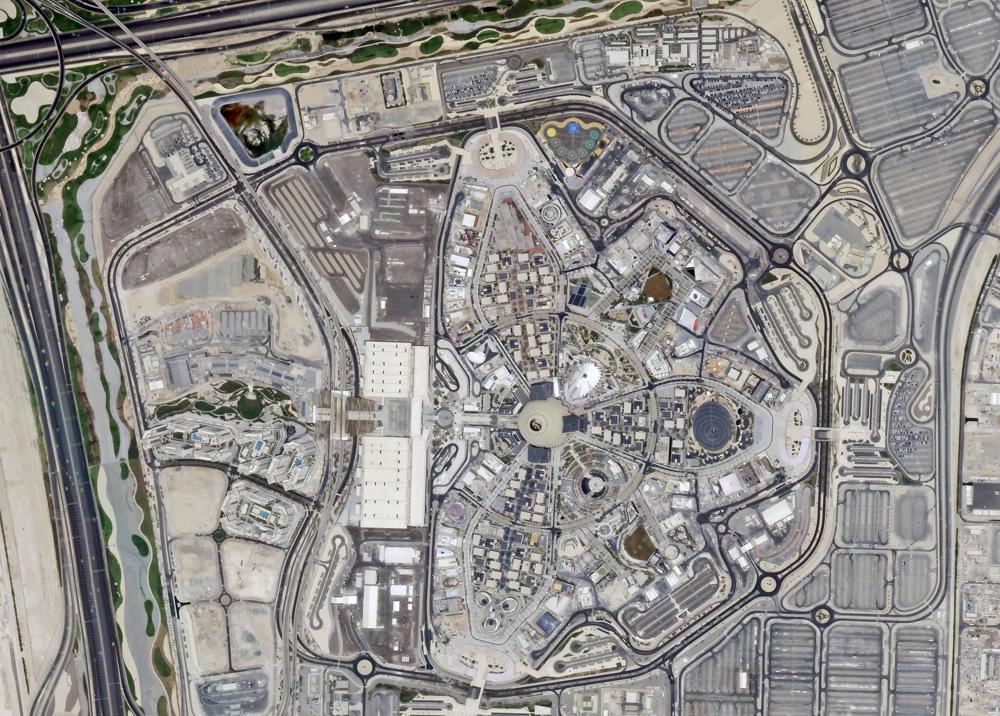

In this Aug. 8, 2021 satellite photo taken by Planet Labs Inc., the site of Expo 2020 is seen in Dubai, United Arab Emirates. Delayed a year over the coronavirus pandemic, Dubai’s Expo 2020 opens this Friday. It will put this city-state all-in on its bet of billions of dollars that the world’s fair will boost its economy. (Planet Labs Inc. via AP)

DUBAI, United Arab Emirates (AP) — A computer-graphic-soaked advertisement featuring Australian actor and Hollywood heartthrob Chris Hemsworth beckons the world to Dubai’s upcoming Expo 2020, promising a “world of pure imagination” as children without facemasks race across a futuristic carnival scene.

Reality, however, crashes into the frame in all capital-letters caption at the bottom of the screen, saying: “THIS COMMERCIAL WAS FILMED IN 2019.”

Delayed a year over the coronavirus pandemic, Dubai’s Expo 2020 opens on Friday, pushing this city-state all-in on its bet of billions of dollars that the world’s fair will boost its economy. The sheikhdom built what feels like an entire city out of what once were rolling sand dunes on its southern edges to support the fair, an outpost that largely will be disassembled after the six-month event ends in March.

But questions about the Expo’s drawing power in the modern era began even before the pandemic. It will be one of the world’s first global events, following an Olympics this summer that divided host nation Japan and took place without spectators. Though Dubai has thrown open its doors to tourists from around the world and has not required vaccinations, it remains unclear how many guests will be coming to this extravaganza.

For some, Expo 2020 has become a $7-billion metaphor for the United Arab Emirates — a futuristic site to draw the world’s well-to-do, built by low-paid foreign workers, to fête a federation of sheikhdoms where speech and assembly remains strictly controlled.

Expo 2020 declined to make any official available to speak to The Associated Press prior to the opening. The organizers also did not respond to a series of questions by the AP about the event, instead emailing back a brief statement.

“We have built an innovative, people-first community that meets the demands of a new world economy, supported by the latest advances in technology and human-centric design,” the statement said.

Modern wonders are what makes the expos shine since their creation in the 1850s. Paris unveiled its Eiffel Tower at the 1889 fair. Chicago became the “White City” in 1893 as electric lights bathed its world’s fair site, which also boasted the first Ferris wheel. Telephones, television broadcasts and X-rays also wowed crowds.

In recent decades, however, many expos have not received the same attention — or at least not the positive kind. The 1984 world’s fair in New Orleans went bankrupt and required a government bailout. Expo 2000 in Germany drew 18 million visitors, well short of the 40 million expected. Milan’s 2015 Expo saw rioting over corruption allegations.

Dubai, which won the rights to host the Expo in the years after FIFA awarded Qatar the 2022 World Cup, will be the Arab world’s first. It had banked on the Expo providing a needed boost to its economy after its real estate market crashed during the Great Recession.

Auditors EY estimated in 2019 that Dubai would spend $7 billion alone on construction projects for the Expo. Relying on a projection of 25 million visitors, EY estimated a $6 billion boost during the event. EY told the AP it hadn’t updated any of its 2019 figures for the Expo.

But that was before the coronavirus pandemic forced Dubai’s long-haul carrier Emirates to ground its fleet of jumbo jets as lockdowns and quarantines seized the world. While the airline is restarting more flights and hiring thousands of cabin crew members, worldwide travel is still ailing.

The UAE, which has grown closer to China in recent years, likely counted on Chinese visitors to the Expo. Shanghai’s 2010 Expo saw over 73 million visitors, a record. But betting on China seems out at the moment as those returning to the country face weeks of quarantines and testing that can include anal swabs.

In recent weeks, Expo officials have begun referring to an expected “25 million visits” to the site, including those watching events online.

“It’s become ‘How do we do the biggest, the best Expo to the world’s ever seen in the Middle East’ to ‘How do we put on an Expo for a very different world?’” said Robert C. Mogielnicki, a senior resident scholar at the Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington. “Getting to 25 million visitors under the current circumstances seems like a pretty difficult target to meet.”

The Emirates also planned splashy announcements around the Expo, perhaps none bigger than its diplomatic recognition of Israel. After delaying the Expo, the UAE last year went ahead with the recognition anyway.

But the event has also become entangled in politics.

Activists raised concerns over workers’ rights issues, as low-wage laborers from South Asia have long faced abuse in the Emirates and across the rest of the oil-rich Arab states, working long hours in intense heat and humidity. In October 2019, an Expo official acknowledged two workers had been killed on the site, and there had been 43 other “serious incidents” resulting in injuries.

It also remains unclear how many laborers fell ill from the coronavirus. In an abrupt change, Expo officials also in recent days announced visitors will be required to prove they were vaccinated or take a coronavirus test before entry. That’s even as the UAE has one of the world’s top per-capita vaccination rates.

Meanwhile, the European Parliament this month urged nations not to take part in the Expo, citing human rights abuses, the jailing of activists and the autocratic government’s use of spyware to target critics.

“There is systematic persecution of human rights defenders, journalists, lawyers and teachers speaking up on political and human rights issues in the UAE,” the European Parliament said.

While the Emirati Foreign Ministry described the parliament’s statement as “factually incorrect,” even Expo press staff repeatedly tried to force visiting journalists to sign forms that imply they could face criminal prosecution for not following their instructions on site.

In recent decades, however, many expos have not received the same attention — or at least not the positive kind. The 1984 world’s fair in New Orleans went bankrupt and required a government bailout. Expo 2000 in Germany drew 18 million visitors, well short of the 40 million expected. Milan’s 2015 Expo saw rioting over corruption allegations.

Dubai, which won the rights to host the Expo in the years after FIFA awarded Qatar the 2022 World Cup, will be the Arab world’s first. It had banked on the Expo providing a needed boost to its economy after its real estate market crashed during the Great Recession.

Auditors EY estimated in 2019 that Dubai would spend $7 billion alone on construction projects for the Expo. Relying on a projection of 25 million visitors, EY estimated a $6 billion boost during the event. EY told the AP it hadn’t updated any of its 2019 figures for the Expo.

But that was before the coronavirus pandemic forced Dubai’s long-haul carrier Emirates to ground its fleet of jumbo jets as lockdowns and quarantines seized the world. While the airline is restarting more flights and hiring thousands of cabin crew members, worldwide travel is still ailing.

The UAE, which has grown closer to China in recent years, likely counted on Chinese visitors to the Expo. Shanghai’s 2010 Expo saw over 73 million visitors, a record. But betting on China seems out at the moment as those returning to the country face weeks of quarantines and testing that can include anal swabs.

In recent weeks, Expo officials have begun referring to an expected “25 million visits” to the site, including those watching events online.

“It’s become ‘How do we do the biggest, the best Expo to the world’s ever seen in the Middle East’ to ‘How do we put on an Expo for a very different world?’” said Robert C. Mogielnicki, a senior resident scholar at the Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington. “Getting to 25 million visitors under the current circumstances seems like a pretty difficult target to meet.”

The Emirates also planned splashy announcements around the Expo, perhaps none bigger than its diplomatic recognition of Israel. After delaying the Expo, the UAE last year went ahead with the recognition anyway.

But the event has also become entangled in politics.

Activists raised concerns over workers’ rights issues, as low-wage laborers from South Asia have long faced abuse in the Emirates and across the rest of the oil-rich Arab states, working long hours in intense heat and humidity. In October 2019, an Expo official acknowledged two workers had been killed on the site, and there had been 43 other “serious incidents” resulting in injuries.

It also remains unclear how many laborers fell ill from the coronavirus. In an abrupt change, Expo officials also in recent days announced visitors will be required to prove they were vaccinated or take a coronavirus test before entry. That’s even as the UAE has one of the world’s top per-capita vaccination rates.

Meanwhile, the European Parliament this month urged nations not to take part in the Expo, citing human rights abuses, the jailing of activists and the autocratic government’s use of spyware to target critics.

“There is systematic persecution of human rights defenders, journalists, lawyers and teachers speaking up on political and human rights issues in the UAE,” the European Parliament said.

While the Emirati Foreign Ministry described the parliament’s statement as “factually incorrect,” even Expo press staff repeatedly tried to force visiting journalists to sign forms that imply they could face criminal prosecution for not following their instructions on site.

Copyright 2021 Associated Press. All rights reserved.