Amanda and David Wood stand as their children, twins Ruby and Lola, and Ethan sit on the porch of their family home in Toronto, Canada, on Monday, July 12, 2021. When Amanda heard that hundreds of coronavirus shots were available for teens, only one thing prevented her from racing to the vaccination site at a Toronto high school – her 13-year-old daughter’s fear of needles. (AP Photo/Kamran Jebreili)

HARARE, Zimbabwe (AP) — When mother-of-three Amanda Wood heard that hundreds of coronavirus shots were available for teens, only one thing prevented her from racing to the vaccination site at a Toronto high school — her 13-year-old daughter’s fear of needles.

Wood told Lola: If you get the vaccine you’ll be able to see your friends again. You’ll be able to play sports. And enticed by the promise of resuming a normal, teen life, Lola agreed.

In Zimbabwe, more than 8,000 miles (13,000 kilometers) and a world away from Canada, immunity is harder to obtain.

On a recent day, Andrew Ngwenya sat outside his home in a working-class township in Harare, the capital, pondering how he could save himself and his family from COVID-19.

Ngwenya and his wife De-egma had gone to a hospital that sometimes had spare doses. Hours later, fewer than 30 people had been inoculated. The Ngwenyas, parents of four children, were sent home, still desperate for immunization.

“We are willing to have it but we can’t access it,” he said. “We need it, where can we get it?”

The stories of the Wood and Ngwenya families reflect a world starkly divided between vaccine haves and have nots, between those who can imagine a world beyond the pandemic and those who can only foresee months and perhaps years of illness and death.

In one country, early stumbles in the fight against COVID-19 were overcome thanks to money and a strong public health infrastructure. In the other, poor planning, a lack of resources and the failure of a global mechanism intended to share scarce vaccines have led to a desperate shortage of COVID-19 shots — and oxygen tanks and protective equipment, as well.

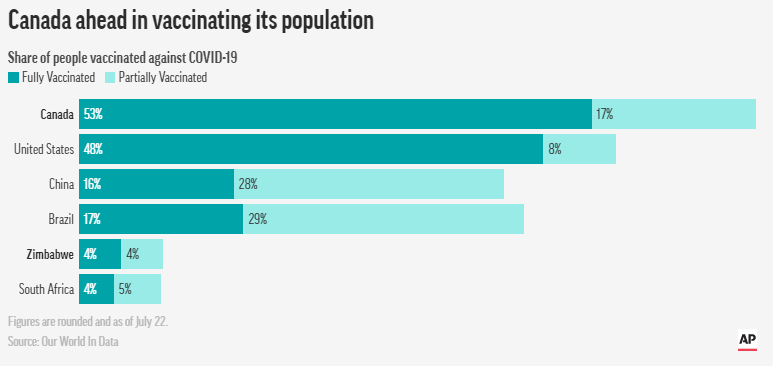

With 70% of its adult population receiving at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine, Canada has among the world’s highest vaccination rate and is now moving on to immunize children, who are at far lower risk of coronavirus complications and death.

Meanwhile, only about 9% of the population in Zimbabwe has received one dose of coronavirus vaccine amid a surge of the easier-to-spread delta variant, first seen in India. Many millions of people vulnerable to COVID-19, including the elderly and those with underlying medical problems, are struggling to get immunized as government officials introduce more restrictive measures.

Ngwenya said the crush of people trying to get vaccinated is disheartening.

“The queue is like 5 kilometers (about 3 miles) long. Even if you are interested in a jab you can’t stand that. Once you see the queue you won’t try again,” he said

Vaccines weren’t always plentiful in Canada. With no domestic coronavirus vaccine production, the country got off to a sluggish start, with immunization rates behind those in Hungary, Greece and Chile. Canada was also the only G7 country to secure vaccines in the first round of deliveries by a U.N.-backed effort set up to distribute COVID-19 doses primarily to poor countries known as COVAX.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said it had always been Canada’s intention to secure vaccines through COVAX, after investing more than $400 million in the project. The vaccines alliance, Gavi, said COVAX was also meant to provide rich countries with an “insurance policy” in case they didn’t have enough shots.

COVAX’s latest shipment to Canada — about 655,000 AstraZeneca vaccines — arrived in May, shortly after about 60 poor countries were left in the lurch when the initiative’s supplies slowed to a trickle. Bangladesh, for example, had been awaiting a COVAX delivery of about 130,000 vaccines for its Rohingya refugee population; the shots never arrived after the Indian supplier ceased exports.

Canada’s decision to secure vaccines through the U.N.-backed effort was “morally reprehensible,” said Dr. Prabhat Jha, chair of global health and epidemiology at the University of Toronto. He said Canada’s early response to COVID-19 badly misjudged the need for control measures including aggressive contact tracing and border restrictions.

“If not for Canada’s purchasing power to procure vaccines, we would be in bad shape right now,” he said.

Weeks after the COVAX vaccines arrived, more than 33,000 doses were still sitting in warehouses in Ottawa after health officials recommended Canadians get shots made by Pfizer-BioNTech or Moderna instead — of which they had bought tens of millions of doses.

The Wood children got the Pfizer vaccine. When Canada began immunizing children aged 12 and over, Wood, who works with children in the entertainment industry and her architect husband didn’t hesitate.

Wood said her children, who are all avid athletes, have been unable to play much hockey, soccer or rugby during repeated lockdowns. Lola has missed baking lemon loaves and chocolate chip cookies with her grandmother, who lives three blocks away.

“We felt we had to do our part to keep everyone safe, to keep the elderly safe, and to get the economy going again and the kids back to school,” she said.

In Zimbabwe, there is no expectation of a return to normal anytime soon, and things are likely to get worse — Ngwenya worries about government threats to bar the unvaccinated from public services, including transport.

Although Zimbabwe was allocated nearly 1 million coronavirus vaccines through COVAX, none have been delivered. Its mix of purchased and donated shots — 4.2 million — consist of Chinese, Russian and Indian vaccines.

Official figures show that 4% of the country’s 15 million population are now fully immunized.

The figures make Zimbabwe a relative success in Africa, where fewer than 2% of the continent’s 1. 3 billion people have been vaccinated, according to the World Health Organization. Meanwhile, the virus is spreading to rural areas where the majority live and health facilities are shambolic.

Ngwenya is a part-time pastor with a Pentecostal church; he said he and his flock have had to rely on their faith to fight the coronavirus. But he said people would rather have vaccines first, and then prayer.

“Every man is scared of death,” he said. “People are dying and we can see people dying. This is real.”

Cheng reported from London. Lori Hinnant in Paris contributed to this report.

Copyright 2020 Associated Press. All rights reserved.