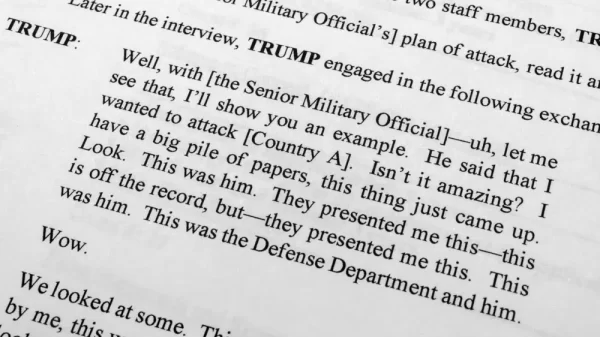

FILE – In this May 3, 2020 file photo, Veneuzuelan security forces guard the shore and a boat in which authorities claim a group of armed men landed in the port city of La Guaira, Venezuela, calling it an armed maritime incursion from neighboring Colombia. Yacsy Álvarez, a woman who was charged in Colombia with helping organize the attempted armed invasion to overthrow Venezuela’s socialist government, says Colombian authorities were aware of the plotters’ movements and did nothing to stop them and that she’s being made a scapegoat for the sins of others who abandoned the would be rebels. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix, File)

MIAMI (AP) — From a windowless cell in a maximum-security prison in Colombia, Yacsy Álvarez awaits trial on charges she helped organize an attempted armed invasion to overthrow the government in neighboring Venezuela.

Álvarez was a translator and business partner of Jordan Goudreau, the former American Green Beret whose ill-fated plan to depose Venezuela’s Nicolás Maduro with a ragtag army he allegedly helped train in the jungles of Colombia ended in disaster last year.

Prosecutors in Colombia said Álvarez helped smuggle weapons to the volunteer army. But she claims she’s being made the scapegoat for the sins of others, including U.S.-backed Venezuelan opposition leader Juan Guaidó, who distanced himself from the self-declared freedom fighters. Last month, her attorney asked prosecutors to add Guaidó as a co-conspirator in the case.

She’s also lashing out at her accusers in Colombia, who she claims were in contact with the plot’s Venezuelan ringleader. Despite being aware of the soldiers’ movements, she said, Colombian authorities did nothing to stop them — even after Maduro’s vice president, a full seven months before the raid, announced the coordinates of the rebels’ safe houses from the floor of the United Nations General Assembly.

“I’ve got no military training, no political experience, no economic resources,” said Álvarez in the brief jail-cell interview from prison in Medellin. “They grabbed me, the most ignorant, to clean up the dishes broken by others.”

Álvarez’s claims raise new questions about the role of staunch U.S. ally Colombia in the so-called Operation Gideon — or the Bay of Piglets, as the bloody fiasco came to be known. The failed attempt last May to ignite an uprising ended with six insurgents dead and two of Goudreau’s former Special Forces buddies behind bars in Caracas.

Colombia, whose security forces are among the top U.S. partners in the world, has steadfastly denied knowingly serving as a staging ground for the incursion, just as the U.S. has insisted it was unaware of any illicit activities.

But Álvarez said the man coordinating the clandestine effort, retired Venezuelan army Gen. Cliver Alcalá, had been in contact with Colombia’s intelligence services ever since he arrived in the country in 2017 following a failed barracks conspiracy inside Venezuela.

The information matches findings of an AP investigation last year that the always loquacious Alcalá openly touted his plans for an incursion and appealed for support in a June 2019 meeting with two agents from Colombia’s National Intelligence Directorate, or DNI.

Alcalá at the meeting in a hotel in Medellin also boasted about his relationship with Goudreau, describing him as a former CIA agent, according to a former Colombian official familiar with the conversation. But when the CIA in Bogota denied any link to Goudreau, Alcalá was told by his handlers to cease all talk of an invasion or face expulsion, the former official said.

PLOTTER OR DOUBLE AGENT?

Nine months after Operation Gideon became a laughingstock on social media, a full account of how it was organized and what led to its unraveling remains cloaked behind questionable confessions and propaganda ploys from Caracas as well as silence and subterfuge from Maduro’s opponents.

Álvarez, 39, has been portrayed in Colombia media as something of a Venezuelan Mata Hari, alternately accused of conspiring to overthrow Maduro or working as a double agent to sabotage the operation from behind enemy lines. But in her telling, her only crime is having come to the aid of the forlorn troops when Guaidó and Colombia, after encouraging the deserters and offering them free housing and assistance, abandoned the men.

She was arrested along with three other Venezuelans last September following a five-month investigation into the arming and training of an exile militia on Colombian soil.

Colombian President Iván Duque said at the time the four were “presumably promoted and financed by Maduro’s dictatorial regime” although so far authorities haven’t presented any hard evidence establishing such links.

Álvarez served as Goudreau’s translator during his visits to Colombia and the two opened an affiliate of his small Florida security firm Silvercorp, in mid-2019. It listed its address at an upscale hotel in Barranquilla, according to Colombian public records.

She also flew with Goudreau and the two other former Green Berets — Luke Denman and Airan Berry — to Barranquilla aboard a Cessna jet belonging to her boss, businessman Franklin Durán, who has a long history of deal-making with the Venezuelan government. At the time, Álvarez was living in the Caribbean coastal city and working as a director in a unit of Durán’s auto lubricants company.

Durán was arrested in May by Venezuelan authorities, accused of financing the plot. Through his lawyers, he has denied any involvement. But Maduro’s opponents have pointed to Durán’s murky past — he spent four years in a U.S. jail for working as a foreign agent of Hugo Chávez to cover up bulk cash contributions to Argentina’s former president — as evidence that the mission had been co-opted.

Wherever his loyalties lie, Álvarez said it was Durán who put her in touch with Alcalá, who he knew for years.

Álvarez said the Colombian authorities were intimately aware of what was going on and appeared to be supportive if not directly involved. At one point, Alcalá introduced her to his longtime handler at the DNI, someone identifying himself as “Franklin Sánchez,” which she now believes was a pseudonym.

At no time did she suspect she was under investigation. Instead, she claims it was Sánchez who tried to protect her, urging her to change residences due to possible threats originating from the Maduro-controlled elite police unit known as the Special Action Forces. She gave the same explanation to her lawyer, Alejandro Carranza, in a recorded conversation from jail on Nov. 26, a copy of which the attorney provided to the AP.

The threat is also referenced in a letter, also provided by Carranza, sent by the DNI a month before her arrest to prosecutors urging them to take “urgent” action to prevent her from being harmed or fleeing illegally to Panama. The letter, which is labeled “secret,” was written at the request of the DNI’s director, retired Vice Admiral Rodolfo Amaya.

She also claims to have spoken via videoconference for three hours to agents from the FBI, who have a parallel investigation into whether Goudreau broke U.S. laws requiring State Department approval for American companies supplying military training or equipment to foreign persons. During the meeting, she says she pleaded with the FBI to protect her mother, who remains in Venezuela, from retaliation by Maduro.

U.N. SPEECH

Colombia’s DNI in a statement said it had no prior knowledge of plans for a military incursion nor any information about Alcalá’s relationship with Goudreau. It also denied ever having any contact with Álavrez, to warn her of threats or otherwise, but didn’t dispute the authenticity of the letter sent to prosecutors about her movements.

But numerous public statements from Maduro’s government, as well as police reports in Colombia of suspicious activity by Venezuelan military deserters, indicate the plot was hidden in plain sight.

On Sept. 27, 2019, Venezuela Vice President Delcy Rodríguez delivered a blistering speech against Colombia at the U.N. General Assembly in which she revealed the location of what she said were three safe houses where soldiers were being trained to oust Maduro. Hours later, the Venezuelan government broadcast on social media the address and a photo taken from Google Earth of one of the houses — what it called “Camp Two” — in the coastal city of Riohacha. Days earlier, her brother, then Communications Minister Jorge Rodríguez, had provided the same information.

The simple concrete home on an unpaved dusty street was rented for around $700 a month on July 1, 2019, by two Venezuelans, according to a copy of the rental contract provided to the AP by the owner. One of the men, Luis Gómez Penaranda, was arrested two months later in Venezuela for allegedly transporting C-4 explosives for a planned bombing of government buildings. In a videotaped confession that was heavily promoted by Maduro’s government, Penaranda fingered Alcalá and one of Álvarez’s co-defendants, Rayder Russo, as the architects of the thwarted attack. Penaranda was freed last year as part of a mass release of government opponents.

Dilarina Mendoza, the home’s owner, said the renters presented paperwork identifying themselves as members of an accredited religious organization, the Mahanaim Foundation, a reference to a Biblical village meaning “two camps” in Hebrew. She said Álvarez, whom she identified in photos, was with them and the one who paid the first month’s rent. On one occasion she saw Álcalá at the house as well as an American in a baseball cap whom she was unable to identify.

From the outset, the tenants fell behind in rent even as ever-larger numbers of Venezuelans crowded into the house, sleeping on metallic bunk beds they purchased. Repeatedly she was told they were waiting for cash to be sent from their brethren in the U.S. Finally, in late October, she filed a police report — a copy of which she also provided — claiming about $2,000 in unpaid rent and expenses.

“I had to kick them out. I was so angry because they wouldn’t leave,” said Mendoza, who said she never suspected they were up to anything nefarious. “On top of that, they left the house a mess and destroyed my marble floor.”

Once evicted, the group of around 20 men moved to similarly downscale quarters 2 kilometers (about 1 mile) away. Police searched the new house on March 26, 2020 — more than a month before the botched Venezuela invasion. The house was uninhabited, but inside they found Venezuelan military uniforms, maps of key states, and nine security cameras among mattresses strewn across the floor, according to a police report obtained by the AP. There were also receipts of small Western Union transfers — one for $48.75 — from other known conspirators among ex-Venezuelan soldiers living in Miami. The police report is referenced in the arrest warrant against Álvarez, a copy of which was provided by her lawyer.

It’s unclear what prompted the raid. But it’s possible authorities were already suspicious even if they were unwilling — or unable — to neutralize the plot and prevent the bloodbath that would soon take place. Three days earlier, on March 23, police seized a cache of 26 assault rifles and tactical equipment it was later revealed were dispatched by Álvarez and destined for the rebels in the desert-like La Guajira peninsula that Colombia shares with Venezuela.

By now, the mission had been thoroughly infiltrated and Maduro’s government couldn’t help but gloat. On March 28, socialist party boss Diosdado Cabello, the eminence grise of Venezuela’s vast Cuban-trained intelligence network, for the first time named Álvarez, Alcalá, and Goudreau and others on state TV for allegedly spearheading a “mercenary” plot to oust Maduro.

“What has the Colombian government done? Nothing, because they are accomplices,” said Cabello.

Ramiro Bejarano, a former Colombian intelligence chief, said Álvarez’s statements are a further embarrassment for Colombian authorities who in their enthusiasm to see Maduro removed overlooked how easily Alcalá’s improvised plan could backfire into what it ultimately became: a hard-to-explain political mess for the Venezuelan opposition and its foreign backers.

“They were either complicit or completely negligent in not shutting it down,” said Bejarano, now a columnist critical of the current government in Bogota. “But it’s impossible they didn’t know what was going on right under their noses.”

U.S. INVOLVEMENT?

Alcalá, a former acolyte of the late Hugo Chávez who broke with Maduro when he became president in 2013, did not partake in the incursion. On March 26 — three days after the cache of weapons was intercepted — federal prosecutors in New York unsealed charges against him, Maduro, Cabello and others for allegedly conspiring with Colombian rebels to ship large quantities of cocaine to the U.S. A $10 million reward was announced for information leading to Alcalá’s arrest — a surprise reversal for an outspoken Maduro critic who had been in contact with Colombian intelligence for years.

But before turning himself in, Alcalá took responsibility for the weapons that Álvarez allegedly helped transport, saying they belonged to the “Venezuelan people.” He also lashed out against Guaidó, accusing him of betraying a contract signed with “American advisers” to remove Maduro from power.

The U.S. has denied any direct role in the attempted Venezuelan raid. Elliott Abrams, who was the Trump administration’s envoy for Venezuela, said last year, in a written response to questions posed by Sen. Chris Murphy, that the only knowledge he and others in the State Department had of Silvercorp’s activities in Colombia came from inquiries by the AP.

Abrams said he had no knowledge of Goudreau’s alleged efforts to obtain weapons nor was he made aware of any meetings between Guaidó representatives and security contractors on U.S. soil related to such an undertaking.

Meanwhile, Guaidó has disputed the authenticity of his signature on an agreement presented by Goudreau detailing a snatch and grab operation against Maduro. The two Miami-based aides who did acknowledge signing the document said they broke off all contact with Goudreau almost six months before the suicide mission was launched.

Goudreau has acknowledged plowing ahead alone, but in October nonetheless sued one of Guaidó’s aides, political strategist JJ Rendon, for $1.4 million, alleging breach of contract. His 133-page complaint reads like an intrigue-filled Netfix series involving everything from clandestine airstrips to aides to Vice President Mike Pence. In it, Goudreau asserts, without evidence except a few inconclusive meetings he had with two Trump officials, that that the ”Álcalá plan” had been approved by the U.S. government.

The FBI, however, has been investigating Goudreau for weapons trafficking, U.S. law enforcement source told the AP last year. In May, it seized $50,000 from him when it raided a Miami-area apartment where he was residing, his attorney told the AP. No reason was given for the seizure although the FBI has since decided to return the funds, the attorney said.

“We believe the raid was conducted in order to provoke a violent response,” Gustavo Garcia-Montes told the AP, adding that his client had already been in contact and was cooperating with investigators. Neither Goudreau nor anybody else has been charged in the matter.

HEROES TO SOME

Back in Colombia, Álvarez and her co-defendants have so far been the only ones held accountable for Operation Gideon.

While Álvarez has vowed to fight the charges, her three co-defendants are considering a plea deal. Álvarez’s attorney said the men are shielding Guaidó, citing as evidence the fact that he was previously a leader in an anti-Maduro party and since migrating to Colombia has been referred cases by the Guaidó-appointed embassy in Bogota. The attorney, Eduardo Cespedes, says he’s just looking to protect his clients from a long jail sentence, but is confident he can beat the charges if the case goes to trial.

To some, Álvarez and her co-defendants remain heroes.

“In Venezuela, everyone fights the dictatorship on Twitter, but these brave men and woman actually risked their lives,” said retired Venezuelan Capt. Javier Nieto, a longtime conspirator who appeared in a video alongside Goudreau in Florida the day of failed beach raid to urge restraint. “Since it didn’t work out, Colombia to save face in the international community had to make arrests. So they grabbed whoever they could find while the cowards who betrayed their promises remain untouched.”

The evidence against Alvarez includes footage from security cameras in an apartment building showing her handing off heavy bags to a person who would be caught hours later transporting the weapons.

She claims she didn’t know what was inside the bags, which she said had been dropped off at her apartment by several of the plotters on instructions from Alcalá while she was in Spain.

“All I tried to do was help some Venezuelan soldiers who trusted and believed in Juan Guaidó’s word when he asked them to join him on the right side of history,” said Álvarez on the verge of tears as she rushes to finish the call before being returned to her dark cell. “If I have to pay 15 years of jail for that, so be it.”

AP investigative researcher Randy Herschaft in New York contributed to this report.

Copyright 2020 Associated Press. All rights reserved.

Source: https://apnews.com/article/yacsy-alvarez-anti-maduro-plot-221bb4d245603ff192b8c207389546c6